Project: EEI Building at Tokyo Institute of Technology

Location: Tokyo, Japan

Architecture: Yoshiharu Tsukamoto Laboratory

Photography: Tomio Oohashi

In the wake of Japan’s 2011 natural disaster, Tokyo Tech’s EEI Building merges technical prowess with architectural innovation, producing a hybrid power station and educational facility that could play a role in revitalising the national grid.

In 2012 the Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech) completed its flagship Energy and Environment Innovation (EEI) Building. This is the first purpose-built facility on the Ookayama campus, dedicated to multidisciplinary research into energy science. Appropriately, given that focus, it will be entirely energy self-sufficient, independent of local utilities. The statistics are remarkable, as is the aim: to generate over 5200 kilowatt hours during the course of an eight-hour day. It’s impressive enough that this will allow for a projected 60 per cent reduction in CO2 emissions compared with their previous building. As well, though, that’s also enough power to run 425 houses in a single day.

This unique project has imbued the university with an air of strategic foresight, especially considering the nature of national events in the lead up to its completion. There were two key moments. Critically, in the chaotic aftermath of Japan’s 2011 earthquake and tsunami, then-Prime Minister Naoto Kan announced an ambitious plan: to create the world’s first national solar array through compulsory installation of solar panels for all buildings and houses by 2030. This brought solar power generation to the fore in Japan’s debate over alternative, private energy production in the wake of the Fukushima meltdown.

Then, on 6 May 2012, operations were suspended on the last of Japan’s 50 nuclear reactors, resulting in a 30 per cent drop in the country’s available power supply. Japan is now at a critical juncture, and with increased dependence on imported fossil fuels, the research and development that institutions and corporations make in carbon-neutral, alternative energy may well be adopted nationally.

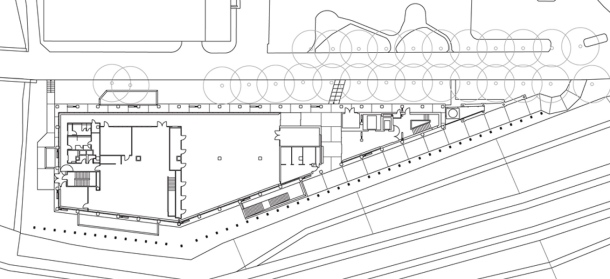

The EEI Building’s multifaceted design features four primary elements: a seven-storey building; a solar envelope covering the roof and the south and west elevations; an expansive wedge-shaped atrium; and the rooftop power management and storage system. Across all seven floors (9500 square metres), students, faculty and staff have immediate access to direct sunlight and seasonal changes in climate no matter which floor, and balconies at every level on the north elevation offer proximity to nature (even on the seventh floor) in the form of the gingko trees lining the site’s perimeter. Meanwhile, the building’s ‘seismic response-controlling structure’ places large, energy-absorbing braces in the stairwell and at diagonal intervals on its three major exterior walls, forming a ‘basket frame’ able to withstand large earthquakes.

The three-pronged design team comprised Yoshiharu Tsukamoto (Atelier Bow-Wow), whose research laboratory was responsible for the overall design; Toru Takeuchi’s lab, responsible for structural engineering; and Manabu Ihara’s lab, charged with developing the building’s environment and energy systems.

Although this isn’t the first building to be constructed from Tsukamoto’s lab, it is actually the first independent of his practice. Even so, its subtle characteristics can be seen as an aggregation of the research and design activities of Atelier Bow-Wow (Tsukamoto and Momoyo Kaijima), from its purpose as a ‘cross-categorical hybrid’ (both power station and educational facility) to the ‘stubbornly honest’ response to its programmatic and technological requirements (elements identified in Tsukamoto and Kaijima’s 2001 book, Made in Tokyo, about Tokyo’s ‘no-good architecture’ of ‘anonymous buildings’).

Yet the aesthetic is elevated beyond generic. Enfolding the south and west elevations and the roof, the solar envelope demonstrates subtle sensitivity to cultural context. In a befitting formal metaphor, it draws inspiration from inakake, the large, wood drying racks used in traditional rice production, but it also pays homage to the great modern architect Kiyonori Kikutake, similarly inspired in his design for the famous 1963 administrative building for the Shinto shrine, Izumo Taisha.

At a distance, the south facade’s semi-translucent pattern appears to be a decorative lattice, although close inspection reveals repeating bands of mounted solar panels. Rows are angled at 30 degrees for the winter solstice, while panels mount flush to the structure at 78 degrees for the summer solstice. The entire envelope comprises 4570 photovoltaic panels covering over 4000 square metres.

The rooftop is the command centre from which power generation, storage and distribution is monitored and managed. This complex system fulfils multiple roles. It manages solar energy generated from the envelope, and efficiently uses exhaust heat through fuel-cell powered, ceramic desiccant air-conditioning and thermal absorption refrigeration. It also takes advantage of natural energy via geothermal heat pumps and a ‘cool tube’ system to maximise cooler air generated in underground pits below the basement floor. Finally, the large atrium, defined by the almost 34-metre void between the building’s south elevation and the semi-detached facade/skin of the solar envelope, assists in drawing heat away from the panels while creating a soaring space for the formal entrance into the facility.

At the time of writing, the summer months were fast approaching in Japan, which means anxiety is mounting as citizens are warned of possible rolling blackouts. The country is in the grip of what’s become known as a setsuden condition, characterised by the constant need to conserve electricity, and prodded along by ongoing reminders that immediate and aggressive measures must be taken by Japan to secure clean, safe, reliable energy sources. And yet relief may be at hand, with the government set to introduce a ‘feed-in-tariff’ scheme, which means utilities will be obligated to purchase electricity at a fixed price for a set period of time from households and companies with their own power-generation systems.

At this stage it’s uncertain whether Tokyo Tech will take part in the scheme, but nonetheless its groundbreaking, emblematic research in the form of the EEI Building will surely be at the forefront of current thinking in this regard, and in the years to come.

Christopher Kaltenbach

Source: Australian Design Review

Hiya! I know this is kinda off topic but I’d figured I’d ask.

Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest writing a blog post or vice-versa?

My website discusses a lot of the same subjects as yours and I feel we could greatly benefit from each other.

If you’re interested feel free to send me an email. I look forward to hearing from you! Great blog by the way!

Since the world around you has uncovered to talk with alone and is beginning to map your needs (the top treasure of marketing and advertising and User Encounter Design and style)”. You may well want to roll out some clothing racks on to the sidewalk, porch, or out in the corridor, depending on your site. While the picket types are really widespread, steel types are also simple to arrive by as they’re generally the most least pricey so if that suits you then have a seem at what is available.